Case-Study: Beyond the Baby. Rethinking Gaze Cueing Through Brad Pitt and Predictive Attention

.png)

How predictive eye-tracking reveals the two stages of gaze cueing, and how creatives can be designed to guide attention to your brand (before launch)

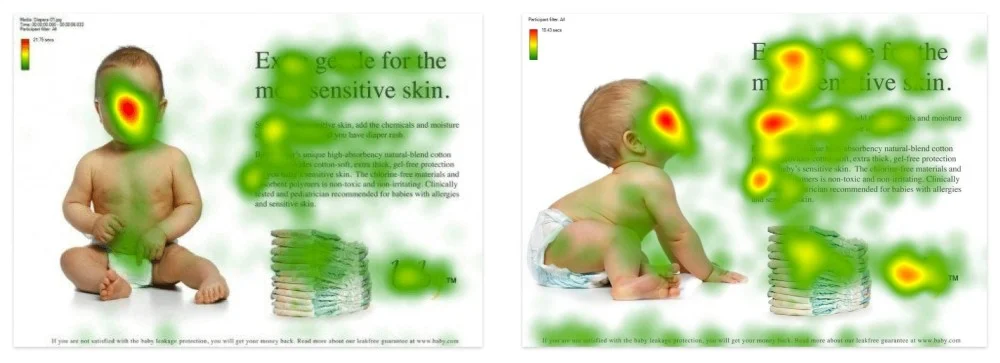

Few neuromarketing principles have travelled as widely as the famous Gaze Cueing Baby. Clean, intuitive, and persuasive: a baby looks at the copy, and viewers follow, responding to the baby’s gaze as a subtle directional cue. The demonstration became shorthand for how attention can be deliberately guided toward a product, brand or CTA, echoed across blog posts and creative playbooks, often without crediting its originator: James Breeze.

Somewhere along the way, the industry embraced his outcome, but lost sight of the mechanism beneath it; a mechanism, once understood, offers the opportunity to design stronger and more intentional attention flows.

This (technical) case-study unpacks the mechanism of gaze cueing. Not to challenge this concept, but to show how attention can be intentionally structured, so design(er)s have the conditions they need for gaze cueing to work optimally in (digital) marketing and advertising.

Why this matters now

Advertising and digital experience environments have changed dramatically since the original demonstration (2009) entered the industry’s vocabulary. Creatives now operate in visually dense layouts, multi-format campaigns, AI-generated assets and shrinking attention windows. Understanding not only that gaze cueing works, but how it begins, unfolds and can be shaped, is essential for designing attention flows that hold up in modern contexts.

This article explores predictive attention, gaze cueing psychology, and AI-based creative analysis through a case study of Brad Pitt × De’Longhi.

What an iconic demonstration did not (need to) show

The Gaze Cueing principle¹ has often been adopted by marketers as a single, instantaneous, universal mechanism, which is not the case. In the famous baby ad, the baby’s face dominates the composition, the background is white and sparse, and the message enjoys a near-monopoly on visual competition. This is clearly visible in the Baby ad below. The viewer could shift attention smoothly from one salient cue to the next. This demonstrates the Gaze Cueing principle perfectly, and shows its potential of creative impact for the advertising industry.

With a more complex digital- and advertising environment in today’s attention economy, ads range from simple to highly creative and visually dense, with multiple elements competing for attention. Lighting, framing, typography, brand assets, motion, and narrative cues all vie for the viewer’s first or second fixation. Under these conditions, the impact of gaze cueing can vary, depending on whether attention is first successfully anchored and stabilized² .

This reflects a broader characteristic of human attention: it does not unfold as a single fluid action. Instead, attention emerges in stages, starting with subconscious, forced fixation and scanning, followed by visual organization and processing, and only later interpretation³.

Breeze’s Baby is most often cited for the outcome of gaze cueing and the resulting viewing behaviour, with less or no attention to the conditions that enable the effect. In practice, gaze cueing is therefore remembered as a universal creative shortcut, rather than as a context-dependent mechanism⁴.

This mechanism unfolds as a staged attention process: first anchoring attention, then guiding it. Together, these stages form the foundation of attention-flow design; a structured way to engineer how viewers move through an ad.

The following diagram outlines these phases of attentional anchoring and attentional guidance within a single viewing sequence:

-min.jpg)

Using this framework, we analyzed a contemporary advertising creative with predictive AI capable of modelling early, subconscious attention at scale. Predictive eye-tracking (predictive attention) estimates where viewers will look in the first seconds of exposure, using trained vision models (without running a live eye-tracking study).

The resulting case study clarifies the two-step nature of gaze cueing and shows how visual hierarchy, attention anchoring, and gaze direction interact in complex advertising environments—offering advertisers a practical way to pre-test and intentionally design for gaze cueing success.

This distinction becomes clearer when applied to a contemporary creative, and to move beyond the familiar baby example, we turn to a stimulus more representative of modern advertising: a celebrity-led brand campaign, Brad Pitt × De’Longhi.

Why Brad Pitt - De’Longhi makes a great case for gaze cueing

The De’Longhi visuals differ from the Breeze demonstration in various ways: they are cinematic, layered, and composed with the visual density typical of premium advertising. Importantly, predictive attention does not recognize Brad Pitt as a celebrity. Instead, it responds to faces as powerful visual and social signals, prioritizing them within the attention structure without interpreting who the person is. This separation between perception and recognition is precisely what clarifies Stage 1 of the sequence: it provides the essence for understanding the first stage of gaze cueing, treating Pitt neutrally, and allowing us to observe the structure of attention without additional cultural weight (which is triggered in the next phase).

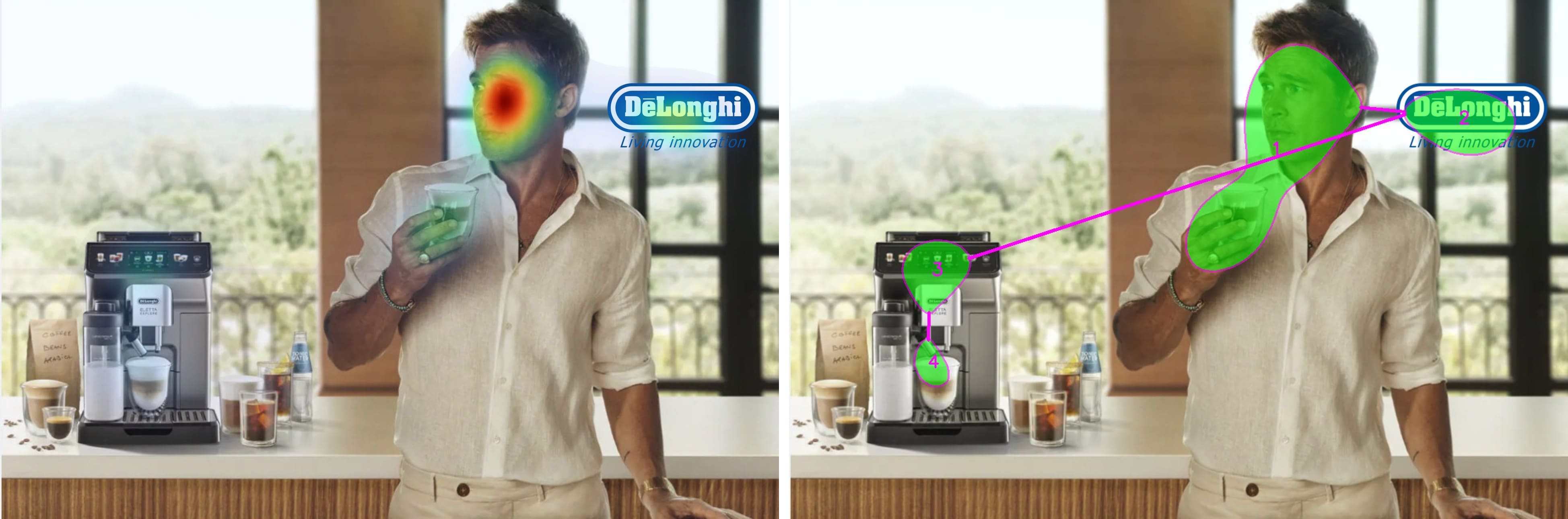

The creative includes the kinds of variables that matter in real campaigns: different logo positions, shifts in negative space, subtle gaze direction, and a product placed with deliberate, but not dominant saliency. By working with three variants (logo absent, logo left, logo right), we can assess where attention begins and how it evolves over the first second(s) of viewing.

Phase 1 (Instant Attention): the precondition for everything that follows

The first stage of visual attention is mechanical rather than interpretive¹. Before recognition or interpretation begins, the visual system allocates attention based on saliency: contrast, edge density, orientation, brightness, and spatial hierarchy, while faces act as especially powerful attractors. Predictive eye-tracking models can approximate this early, pre-interpretive stage because it is largely driven by low-level visual features and face bias.

Across all three De’Longhi variants, the early pattern is remarkably consistent:

• The viewer’s first fixation lands on the face (stopping power).

• The product receives early attention when contrast and proximity support it.

• The logo receives early attention only when its visual weight is sufficiently high.

• The direction of the model’s gaze has no measurable effect in this early window.

This consistency is telling. It shows how a stable and predictable scan path can be established before gaze cueing is expected to occur. The composition organises attention in a way that is consistent with the conditions under which gaze cueing has been shown to operate in live eye-tracking research.

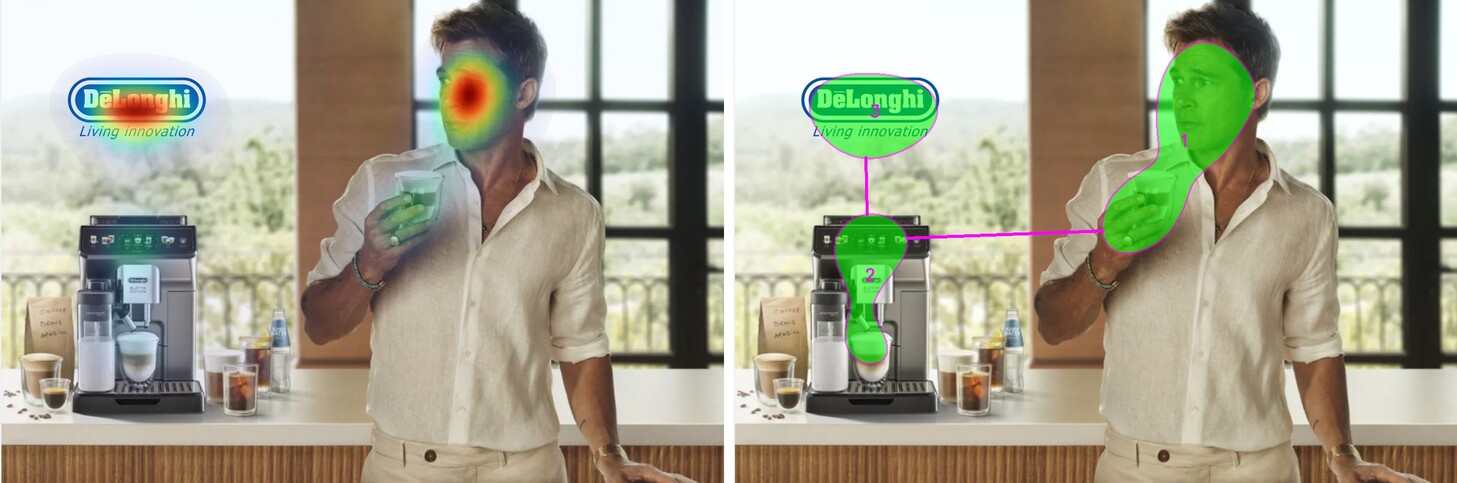

Phase 1 is therefore foundational: it establishes the starting point, the visual hierarchy, and the potential pathways along which gaze cueing can later reinforce attention in real viewing conditions. The Brad Pitt - De’Longhi image (no logo, Pitt's gaze to the left / his right) is the baseline image. The AI heatmaps show that most attention is drawn to the face, the cup in its peripheral glance, then shifting to the De’Longhi coffee machine:

In this phase, the face does not succeed because it is Brad Pitt, but because faces occupy a privileged status in human vision. They are detected early, efficiently, and without semantic interpretation. This aligns with decades of empirical research in vision science and helps explain why the baby demonstration is so often remembered for its outcome, rather than for the attentional conditions that make that outcome possible.

At this point, the question is not yet whether gaze cueing works, but whether the visual system can process the scene with sufficient ease. Beyond where attention lands, how attention is organised matters.

The number of hotspots, their relative size, distance, and sequencing determine how much effort the visual system needs to stabilize the image. This ease of processing is often described as Visual Clarity, and forms an essential precondition for attention flow. If attention is overly fragmented or pulled in competing directions, the system expends resources simply resolving the scene, leaving little capacity for directional cues to exert influence. This diagnostic concept allows us to assess whether a composition is structurally ready to support guided attention. How this plays out becomes visible later in the case study, when logo placement and compositional changes are introduced and compared across variants.

Phase 2 (Guided Attention): where Gaze Cueing Actually begins

Stage two is about what happens after attention has been captured. This is not a single moment, but a progression. First comes a phase of visual organization, where attention begins to move across the composition, guided by spatial relationships, layout, and directional cues. Only after this visual transition does the interpretation follow: meaning is assigned, context is understood, and social signals -such as gaze direction- begin to exert their influence. In other words, gaze cueing does not operate at the instant attention is captured, but in the transition that follows, when attention is organised visually before it is interpreted cognitively.

Once this visual organisation has stabilised and attention is anchored, a different layer of processing emerges: recognition begins and expressions are interpreted. At this point, attention transitions into early engagement, as the viewer starts to infer intention, trajectory, and narrative.

Only now does the direction of the model’s eyes acquire meaning, and only now can gaze cueing take effect as demonstrated in foundational gaze-cueing studies⁵.

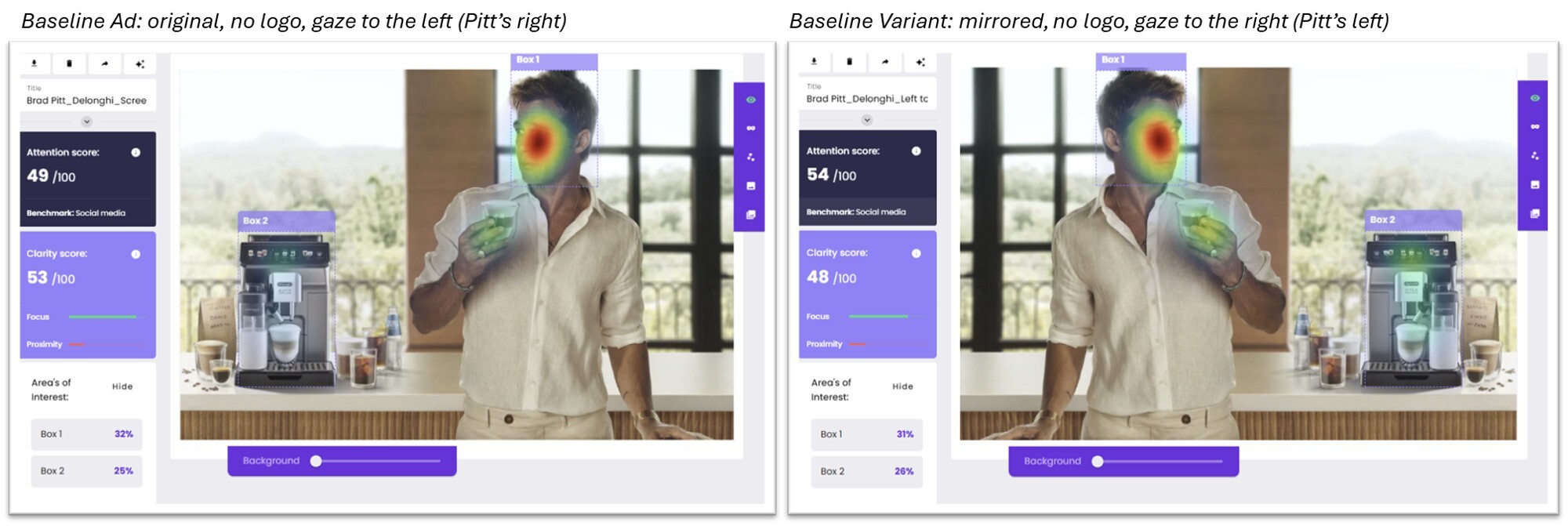

Keep in mind that the design needs sufficient clarity for ease of processing (cognitive load), which is easier for Breeze’s Baby, harder for a more layered ad like De’Longhi. Use Brainsight’s Clarity Score for this analysis.

Unlike the original baby demonstration, that was designed to showcase the directional cue, the Brad Pitt × De’Longhi creative was not constructed as a gaze-cueing example, but as a realistic brand campaign. Precisely because of that, it provides a credible baseline for exploring how gaze cueing can be prepared, tested, and optimized in contemporary advertising environments. With plausible brand placements, multiple focal points, and aesthetic constraints, the Pitt variants do not demonstrate gaze cueing itself. Instead, they show how design can establish a coherent and predictable scan path, one that aligns with the conditions under which gaze cueing is known to emerge at later stages of visual and cognitive processing.

Seen this way, gaze cueing becomes part of a broader practice of attention-flow design, where visual structure and social cues work together to guide how viewers move through an ad. From this staged perspective, gaze cueing is strengthened not by gaze direction alone, but by the deliberate ordering and redistribution of visual stimuli that stabilise attention before it is guided—an interpretation consistent with research on attentional disengagement, visual hierarchy, and staged models of attention.

The Brad Pitt × De’Longhi variants illustrate this transition. The following heatmaps and predictive gaze plots (also referred to as gaze maps or scan paths) show how Stage 1 anchors attention:

In these predictive gaze plots (also often referred to as Gaze Maps or Scan Paths), we observe a subtle, consistent directional tendency that arises only after the face has absorbed the initial fixation, a pattern consistent with gaze cueing dynamics reported in live eye-tracking research. However, it's not instantaneous, but conditional: it is dependent on the groundwork laid by Phase 1 and shaped by the visual plausibility of the scene.

From anchoring to organisation: why clarity matters

Heatmaps reveal where attention first lands, but they do not tell the full story of how easily an image is processed. For gaze cueing to have any chance of working later, attention must not only be captured; it must also remain structured and efficient.

This is where visual clarity becomes critical. Clarity reflects how concentrated or fragmented attention is across the visual field: how many competing hotspots exist, how far they are apart, and whether attention can move through the scene without unnecessary effort.

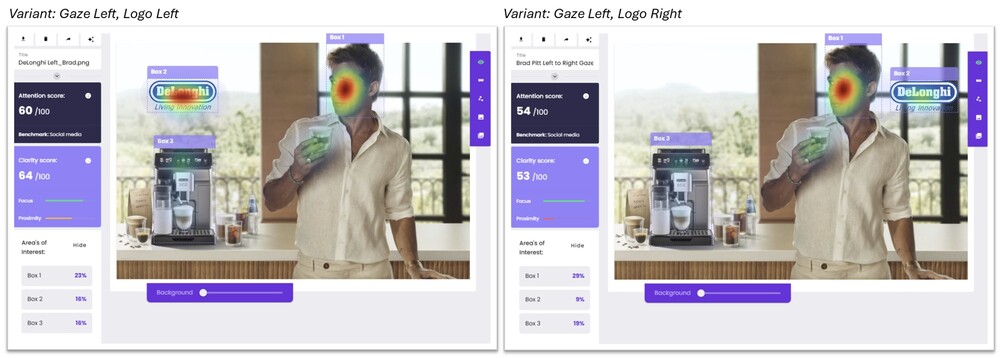

In the Brad Pitt variants, the introduction of the logo along a plausible visual pathway does not disperse attention. Instead, attention becomes more focused and organized. This is reflected in higher clarity scores and more stable attention distribution across the face, brand, and product. The following dashboards make this visible by combining attention distribution (AOIs) with clarity metrics, showing how different placements either reinforce or destabilise the emerging attention flow.

Method note

Predictive attention modelling estimates early, pre-cognitive attention patterns under natural viewing conditions. It does not measure live gaze-following, but evaluates whether visual structure supports gaze cueing as described in established research. All variants were analysed under identical conditions with consistent AOI placement; minor differences were retested and found negligible. Outputs reflect early attention distribution and scan-path structure, while dwell time and conscious gaze following require live research⁶.

Across both gaze directions, placing the logo within the natural field of view increases clarity rather than reducing it. Attention hotspots become fewer, more concentrated, and more predictably connected. This matters because gaze cueing relies on perceptual ease. When attention is overly fragmented or prematurely pulled toward secondary elements, the visual system must work harder to stabilize the scene, weakening the conditions under which directional cues can exert influence.

What the analysis establishes

Taken together, the heatmaps, gaze plots, and clarity metrics show a consistent pattern. Attention is reliably anchored by the face, remains structured as brand elements are introduced, and forms a coherent scan path rather than fragmenting across the scene. Importantly, clarity does not degrade when the logo is added along this path; it improves. This matters because gaze cueing cannot operate in a visually unstable environment. Phase 1 therefore establishes the perceptual conditions under which gaze cueing is known to occur in later stages of processing⁷.

Why This Matters for Creatives

Understanding gaze cueing as a two-stage process has direct implications for creative design. Gaze direction alone cannot compensate for weak structure: if a brand or product lacks saliency, or if a layout is visually cluttered, a model’s gaze will not resolve the problem. Gaze cueing does not create attention pathways from scratch; it reinforces flows that are already viable.

This distinction also clarifies the role of predictive attention modelling. Such tools are not intended to simulate social interpretation or meaning-making. Their value lies in revealing the design architecture of Phase 1—how attention is anchored, distributed, and stabilised—thereby determining whether the conditions for Phase 2 are in place.

Finally, this perspective helps explain the gap between the original research and how it has been absorbed by the industry. Breeze’s live eye-tracking work captured the full trajectory of attention, while advertising practice retained mainly the final behaviour. What was largely overlooked was the preparatory stage: the perceptual anchoring that makes gaze cueing possible. Contemporary predictive modelling does not challenge the established principle; it complements it by making this stage explicit, and therefore designable.

Designing for Both Phases of Attention

If gaze cueing depends on a sequence, then that sequence can be designed for.

In practice, effective gaze cueing tends to emerge when several conditions align. A face first establishes an attentional anchor and emotional tone. Product and brand elements need to sit within perceptual reach of that anchor, rather than competing with it. Gaze direction then reinforces a pathway that already exists in embryonic form, instead of attempting to create one on its own.

When these conditions are met, gaze cueing feels natural, almost inevitable, because it aligns with how viewers already expect attention to unfold. When they are not, the effect weakens or disappears, not because gaze cueing is invalid, but because the visual system never reaches the stage in which it can operate.

Keep in mind that attention is no longer a single moment to be captured, but a temporal flow to be shaped. This perspective allows designers and advertisers to think in terms of attention choreography, rather than static composition. This mindset becomes especially powerful when combined with predictive attention analysis, which makes these early-stage dynamics visible before launch.

The Role of Predictive Attention and AI Gaze Analysis

The first phase of attention is pre-cognitive. Therefore, it can be modelled.

Because the first phase of attention operates below conscious awareness, it can be modelled. Predictive attention analysis captures the structural conditions of Phase 1: saliency distribution, early fixations, and visual clarity. These models do not interpret meaning or social intent; they reveal whether an image affords a stable and intelligible entry point for attention.

AI-based gaze analysis complements this by visualising how attention is likely to progress once interpretation begins. Together, these approaches reflect the two-stage nature of attention itself: one concerned with perceptual anchoring, the other with guided progression. Neither is sufficient on its own, but in sequence they make the mechanism of gaze cueing legible and designable.

The practical implication is not more testing, but earlier and more targeted testing. By optimising Phase 1 before launch, designers can ensure that the conditions for gaze cueing are present when Phase 2 unfolds in real viewing situations. Live A/B testing can then focus on outcomes, rather than compensating for structural weaknesses that could have been addressed upfront.

Implications for Advertisers and Designers

Viewing gaze cueing as a staged process rather than a universal shortcut changes how creative decisions are made. The question is no longer whether gaze direction works, but whether the visual system is given a coherent path to follow. Faces anchor attention, layout and hierarchy stabilise it, gaze direction can then reinforce a trajectory that already exists.

For creative teams, the opportunity lies in orchestration rather than optimisation in isolation. When saliency, structure, and social cues are aligned, gaze cueing becomes a natural extension of the viewer’s own visual expectations. Predictive attention modelling makes this alignment visible before launch, while live testing remains valuable in campaigns where narrative depth or emotional nuance plays a decisive role.

Conclusion

Gaze cueing remains one of the more elegant phenomena in visual cognition, but its elegance can obscure its complexity. The effect Breeze highlighted with his infant subject is perfect, but it was adopted and applied as a shortcut to a social, interpretive stage of attention, forgetting about the perceptual foundation on which that stage depends.

The Brad Pitt × De’Longhi creative reveals that missing first precondition. It demonstrates that before gaze direction can influence behaviour, early attention must be anchored, the visual hierarchy must be coherent, and the pathway must be structurally viable and easy to process (clarity). Once those conditions are met, gaze cueing emerges is more likely to emerge, not as a trick or shortcut, but as a natural continuation of the viewer’s perceptual and interpretive processes.

As designs are never universal and vary by category, format, brand, layout, and creative intent, gaze cueing cannot be applied as a static rule, but is ideally prepared and validated within the specific visual context of each creative. Predictive attention modelling is particularly well suited to this task. By revealing how attention is distributed in the earliest moments of viewing (as shown in this case study), before interpretation and engagement, designers can iteratively test whether a composition establishes the clarity and scan path required for gaze cueing to function later. Rather than assuming that a directional cue will work, teams can validate whether the visual groundwork is in place, adjust it, and only then refine the guiding elements, all without live research.

In practice, this means that gaze cueing is not something to be hoped for, but something that can be prepared, stress-tested, and refined—long before any live campaign data is available.

Sources/ Reference / Footnotes:

Original demonstration of gaze cueing in advertising by Breeze, J. (2009), You look where they look, published on his website Usable World

¹ Friesen & Kingstone (1998); The eyes have it! Reflexive orienting is triggered by nonpredictive gaze, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review

¹ Driver, J., Davis, G., Ricciardelli, P., Kidd, P., Maxwell, E., & Baron-Cohen, S. (1999), Gaze perception triggers reflexive visuospatial orienting, Visual Cognition

¹ Langton, S. R. H., Watt, R. J., & Bruce, V. (2000), Do the eyes have it? Cues to the direction of social attention, Trends in Cognitive Sciences

² Birmingham, E., Bischof, W. F., & Kingstone, A. (2008), Social attention and real-world scenes, Current Biology

³ Wolfe, J. M. (1994), Guided Search 2.0: A revised model of visual search, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review

³ Wolfe, J. M. (2020). Visual Search: How do we find what we are looking for? Annual Review of Vision Science, 6(1), 1–24. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-vision-091718-015048.

⁴ Wedel, M., & Pieters, R. (2008), Eye tracking for visual marketing, Foundations and Trends in Marketing

⁵ Friesen & Kingstone (1998)

⁶ Scientific note on scope: predictive attention models do not measure the underlying neurological command responsible for gaze shifts (the exogenous attentional reflex, typically occurring within ~100–300ms). Instead, they evaluate the structural efficiency of the visual scene, like saliency distribution, attentional anchoring, and clarity to determine whether the creative architecture supports the endogenous biases that enable gaze cueing to translate into an effective visual path. Metrics such as the Clarity Score quantifies this structural readiness rather than reflexive eye movements themselves.

⁷ Wolfe, J. M. (2020). Visual Search: How do we find what we are looking for? Annual Review of Vision Science, 6(1), 1–24. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-vision-091718-015048.

.mp4%20-%20Heatmap.jpg)